Interesting Account of the Venango Oil Region

The Record (West Chester, Pa.), January 3, 1865

A correspondent who has been through the oil region writes from that greasy latitude as follows:

The Oil Region of Pennsylvania

Venango County is, par excellence, the oil region of Pennsylvania. Some attention has recently been given to Clarion County, and other sections of the State, but nothing of consequence has been as yet found outside the limits of Venango County, which may be considered the great oil basin of the State. If a line be drawn nearly through the centre of the county, running from north to south, tending a little west. It will pass along Oil Creek, the center and most productive portion of the oil territory.

From Franklin, a few miles below where Oil Creek joins the river, the Allegheny to the east and French Creek to the West, form a huge “V” with Oil Creek passing down the middle and joining the right arm of the V just above the point of junction. Below this point, the Allegheny stretches, converting the V into a Y.

The center or Oil Creek line is that of the greatest yield at present, the others not having been sufficiently tested to establish their character as large oil producing lines, although enough has been ascertained that oil in considerable quantities exist. The first discoveries of oil were made on Oil Creek. For some time explorations were confined to that line. The success there met with induced others to examine into the oil-producing qualities of the adjoining streams. A number of holes were sunk on the banks of the Allegheny River, French Creek (an affluent of the French), and some of the “runs,” or small streams, tributary to the several creeks.

These wells were put down by hand, by horsepower or by waterpower. The operation In either case being very slow and tedious. Few penetrated lower than the second sand but the disturbed state of the country, and the low price of oil – consequent on the limited demand and the large supply from the flowing wells – discouraged the well-owners. Most of the wells were abandoned without further test when it was found they would not “flow.”

The deserted derricks, standing like monuments of dead hopes and buried fortunes, frighted many a timid speculator who had some thoughts of investing in oil wells, and tended to keep operators closely to the line of Oil Creek.

The result was that the creek was thoroughly explored from Titusville to Oil City, a distance of nearly 20 miles. In that distance the ground is punched, like a strainer, with hole. Most of them exuding oil, but many “dry holes.” From Titusville up, there are also a large number of wells, but as yet they have not been largely productive. If the six miles to be taken that lie about midway between Titusville and Oil City, it will be found that nearly all the flowing wells of notoriety lie within that space.

When oil, that at 15 cents a barrel was allowed to run to waste, rose to seven or eight dollars a barrel, owing to the European demand that at length sprung up. The abandoned wells in the creek were once more put in operation and all the available land taken up in leases. Those who were attracted by the fortunes rapidly and easily made by shrewd or lucky operators. [They] found on coming to the creek to invest that the desirable property was unattainable, and were compelled to turn their attention elsewhere.

The “Runs” or ravines opening into the creek were explored, and were found but little, if any, inferior to the larger portion of the creek oil territory. The success in that direction gave a powerful impetus to the progress of developing new oil territory. Old wells were taken by new parties and on being tested with proper machinery were found to be, in many instances, highly productive. New wells were sunk in spots hitherto looked on with disfavor. The favorable results, sometimes obtained, heightened the excitement.

At last speculators, eager for a chance to make large fortunes in the least possible time, turned their attention to oil lands. That virulent disease known as “oil on the brain” became epidemic, affecting all ranks and conditions of men, and spreading rapidly from city to city until now the whole country burns with oil fever.

Oil Companies

Stock companies for the working of oil lands are already numbered by hundreds. Each day sees fresh accessions to the lists. That many of these companies are mere bubbles, intended only to trap the unwary and fill the pockets of those who go into the adventure “on first principles,” cannot be denied. Therefore, the public should look closely into the character of the managers of a concert before entrusting their loose funds to his keeping. Many, also of those honestly conducted, will prove unremunerative investments, while some will, undoubtedly, obtain a fair return for their enterprise. With regard to the prospects of honestly conducted companies, it is difficult to exercise any judgement.

Speculations in oil wells partake more of the nature of lottery than any other operations that I am acquainted with. This consists, with many, its peculiar charm.

Three weeks careful investigation of the different sections of the oil regions have left me as much in the dark as ever as to what are the best locations or positions for successful oil wells. Territory that now seems unlikely to produce a gallon of oil, may, a few months hence, be among the best oil territory. No sooner is a theory established and rules laid down for the guidance of those intending to sink experimental wells, than some well, put down in defiance of theory and in violation of rules deduced from experience, gives an abundant yield of oil. And knocks all theories and established rules into “pi.” This has been done so frequently that it would be worse than useless for me to theorize on the matter. Or to say that any particular undeveloped territory is or is not likely to yield oil in paying quantities.

The proof of the pudding is in the eating. It is only after a location has been thoroughly tested, that any correct idea can be obtained as to its value as oil territory. In the meantime, all that can be done is to judge from the actual developments in the neighborhood, the surface indications, and the configuration of the land as compared with known oil-bearing locations.

The day of individual enterprise by men or of small means has gone by in the oil regions. The successful working, by capitalists, of wells that had swallowed up the entire funds of their original owners, and left them without means to complete their work, is sufficient evidence of the folly of a man risking his all on one throw. Associations of capital are needed to prosecute the work of exploration. Such associations have taken the task in hand, thus lessening the individual profit. But also decreasing the individual risk.

Increasing Land Value

The result for his movement has been to greatly enhance the value of land throughout the oil regions. Immense profits have been made by all concerned in the transfer. Before reaching the hands of the company who are to operate on it as the bona fide owners, the land frequently doubles or triples in price. The method usually adopted in such transactions is the following:

A speculator looks at a farm in an undeveloped or partially developed neighborhood and inquiries the price. The owner puts from double to quadruple the actual value upon it, and asks, perhaps, $20,000, being from $200 to $300 per acre. The speculator obtains the refusal for 15 or 20 days, paying from $25 to $100 for the privilege. He then endeavors to sell the land to some other speculator for $25,000 to $30,000, or four or five persons club together to take it at that price. On the appointed day the actual purchase is made. The first operator pockets a comfortable “margin.” If he fails to sell, he loses his deposit.

The next step is for the purchaser on first principles to stock the property, organizing a company, putting the capital stock at, say, $100,000, and reserving $25,000 as working capital. The other $75,000 in stock is divided among the partners on first principles as pay for the land so that if the stock sells freely at par, a handsome profit is made even through a liberal proportion of stock be retained as an investment by the original partners. A common proceeding is for the getting up of a company to put in a large amount of undeveloped land, connecting with an interest in some dividend-paying wells on the creek as a “sweetener.” In some cases the stockholder obtains a good investment in this way, whilst in others he is “sweetened.”

To give the full result of my observations in all parts of the Venango oil region during the past three weeks, would be taxing your space too severely. I will therefore confine myself to a general summary.

Oil Creek

Oil Creek, from Oil City up to Titusville, is as full of busy life as ever. While there are fewer large wells than there were some months since there have been a large number of moderately productive wells sunk and put into operation. With the exceptions of the one on the Egbert farm, no new flowing wells of consequence have been struck. The yield of the other flowing well has generally diminished. The scarcity and extremely high price of fuel has tended has tended seriously to embarrass operations and a large proportion of the wells have decreased in production from this cause alone. The sudden cold snap, preventing the running of boats on the river and flats on the creek, has made matters worse in this respect, so that a temporary decline in the production of the creek may be expected.

Above Titusville considerable activity has been manifested. Speculators have been taking hold more or less freely. New derricks have gone up for several miles above the town, and preparations made for testing the value of the territory.

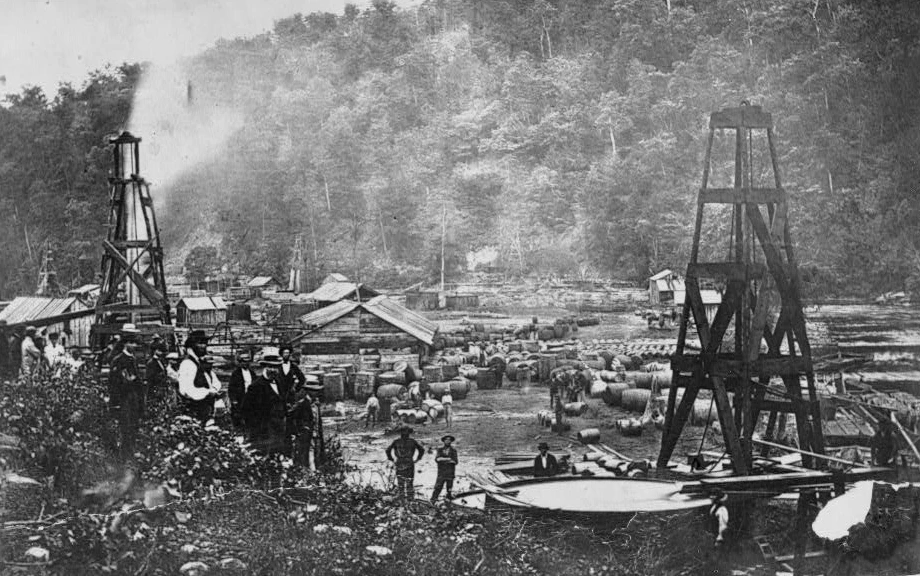

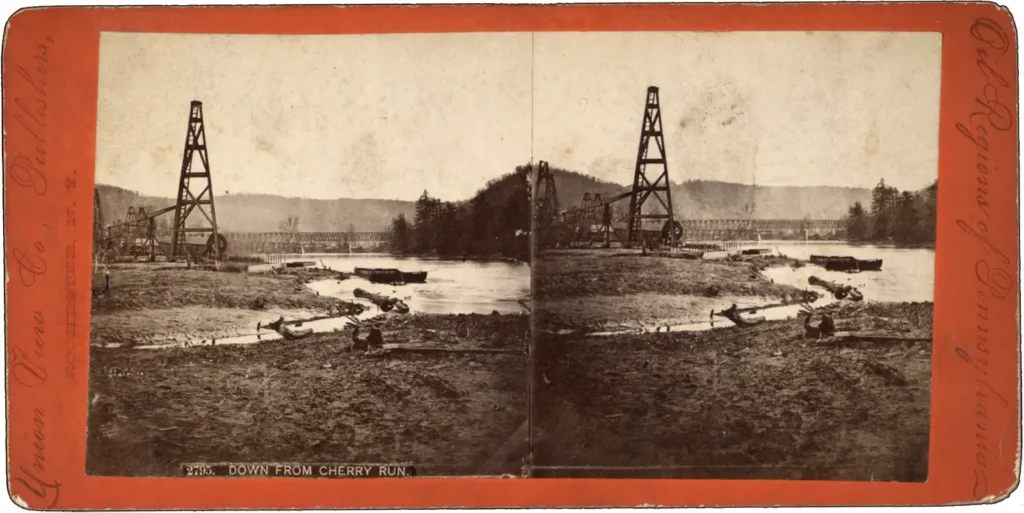

Cherry Run

Cherry Run, which opens from the cast into Oil Creek, about three miles above Oil City, is now full of life and business. The opening of the Reed Well, which has been steadily flowing for weeks at the rate of 280 barrels daily. The subsequent opening of several other wells of less volume has created a wild feeling of speculation of the run. The narrow valley is crowded with wells, already productive, or going down. Even the steep hillsides are dotted with derricks, and some of the wells situated high up the Bluff have already “struck ile.”

It is said that not a single well that has reached the third sandstone on this Run but has found oil. Certain it is, that of the numerous pumping wells I visited on the Run, every one was pumping more or less grease, whilst there are several wells flowing from 50 to 100 barrels daily, in addition to the Reed Well, already mentioned. The run is leased for nearly ten miles from its mouth, the derricks being planted thickly along the valley, although the engines for a large proportion of them are not yet on the ground. The leases on this Run give half the oil to the land interest as is now the usual practice in developed territories. In addition, large houses have in some instances been paid.

Cherry-tree Run

On Cherrytree Run, which opens into the Creek from the west about a mile above Cherry Run, Weikel Run, Benninghoff’s Run, Cornplanter Run, and some other small runs opening into Oil Creek. Active operatives are going on with a view to developing the property, but as yet none of the wells have gone deep enough to afford a test. On Two-mile Run, which enters he Allegheny, some oil has been found and a member of wells are going down.

French Creek

French Creek, which joins the Allegheny at Franklin, seven miles below Oil City, has recently again come into favor as oil territory. Some of the old wells have been cleaned out and rendered productive. Several new wells are going down, and land on the creek has generally been bought up and leased. The oil on French Creek and its tributaries is of a better quality than the average – heavier and valuable as a lubricator. It sells for more than double the price of Oil Creek oils.

Sugar Creek

Sugar Creek, which joins French Creek about three miles above Franklin, has within a few weeks come into note, and new lands have been extensively taken up. Three old wells that produced considerable oil from the second sands one, by clumsy water-wheel contrivances, have been leased by companies, mostly New York and Philadelphia, above Mill City, and Pittsburgh below that point. At Tidioute are the Economite Shallow wells, worked by a religious sect for a considerable time with good success. The next point below is Hickory Creek, where the Hickory Farm Company have a large and valuable tract, and are sinking wells. Several oil-producing wells are on this tract and its vicinity.

Hemlock Creek

At Tionesta and Lower Tionesta there are wells doing a fair business, and preparations for several new wells. Wells dot both sides of the river until President is reached, where extensive preparations are making for developing the territory. Just below is Hemlock Creek. From this point down, there are a number of producing wells, and a still greater number of wells going down. Within a few days, a hundred-barrel well was struck on the Jamison Flats, near the Hemlock. A hundred-barrel flowing well, leased by the Heydrick’s on the Armstrong farm, immediately opposite the celebrated Heydrick’s, flowing well of two or three years since. Pit Hole Creek, Walnut Bend, Horse Neck Creek [Horse Creek] and the line of the river to Oil City are thronged with wells, new and old.

South of Oil City

Below Oil City there are fewer wells in operation until reaching Franklin, below which point a number of wells are working or going down. A number of new companies have obtained possession of the property on both sides of the river, and are working actively.

On the Big Sandy several leases have been taken, and preparations made for sinking new well. East Sandy and Scrubgrass Creek have also been partially leased, although not quite as much in favor yet as the territory higher up the river.