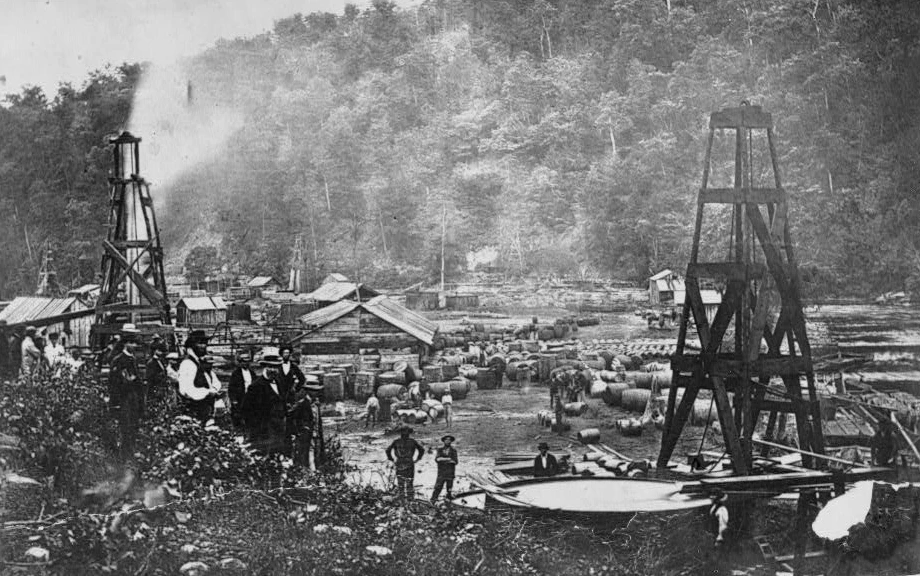

The Pennsylvania Coal Oil Wells

American and Commercial Advertiser (Baltimore, Md.), February 10, 1862

The Titusville Gazette gives the amount of oil shipped from that point for the week before last at 13,168 barrels. That paper also says that the depots at the shipping stations are so full that storage cannot be found, nor can the railroad get it out of the way nearly as fast as it goes forward from the wells. The recommendation of the Venango Spectator, to plug up the wells, seems to have been tried at various places in consequence of the low price of oil. But other wells are yielding. The Van Slyke well has increased from 500 to 1,500 barrels daily.

The following condensation of some oil marvels will assist the reader to understand the subject:

A recent visitor who spent a week in the Pennsylvania oil regions, reports that at Oil City, at the mouth of Oil Creek, on the right bank of the Allegheny, there were over 20,000 barrels of oil on the wharf awaiting shipment to Pittsburgh. At one of the great flowing wells 114 large cisterns were counted, holding 30,000 barrels of oil. The Empire Well is 600 feet deep. The gas forces the oil through hose up to a reservoir 300 feet higher, and saves hauling. Thus the pressure of the gas carries the oil 900 feet.

The writer says:

“The chief of the veins is the Phillips1, which was struck two months since, and yields 3,000 barrels daily. Like the others, it is fitted with a stop-cock, and only allowed to run as the oil can be taken care of. The stop-cock is inserted in the tubing, which is sunk as soon as an oil vein is struck. The bore of this well is five inches in diameter. When the vein was struck, a torrent of oil burst far above the derrick. Three days passed before it could be stopped and brought under control, all the time the stream from it running into Oil Creek.

The lands here are not sold, but rented. The land owner usually receives half the oil. The Phillips Well was leased for a quarter of the oil delivered in barrels. Now that oil is down and barrels up, it would be ruinous to deliver the barrels. Another well is leased for half the oil, but the landowner is to take his share only on Saturdays. The well yields 800 barrels daily, but [without sufficient teams] it is impossible to move more than that amount in a day. The owners get only 800 barrels a week, and the person leasing 400.

About 4,000 barrels are daily sent away. As six barrels make an average load, from two to five days are required for a roundtrip. One can easily estimate the enormous number of teams employed. One party alone pays $3,000 a day for teams to the various railroads, the nearest point being twenty miles distant.

Fleets of flatboats are building to go down the river with the spring freshets. They are from forty to eighty feet long, fourteen feet wide and two feet deep. They are to be drawn up alongside the flowing wells, and by a hose will run full, and then floated down to Pittsburgh, the oil being thus taken to the refineries in bulk. The expense of barrels, which is from $2 to $2.25, being saved.

Hundreds of thousands of dollars have been lost by sinking wells where no oil vein has been struck. One well has reached the depth of 875 feet, and still the boring goes on. A placard on the derrick says, ‘To Oil or to China.’”

A paragraph in an Erie paper mentions that crude petroleum oil sells at Tidioute for twenty cents per barrel. The trouble now appears to be to find a market for all the oil that is produced, but the energy with which the matter has been taken up by good businessmen warrants the belief that it will soon force an adequate market.

The enormous quantities of this oil, together with the great supplies of lard oil from the west, and of coal oil from various quarters will be likely to usurp the place of whale oil. Already the whaling business has fallen off astonishingly, as may be seen by the following telegraphic dispatch from San Francisco:

“The Polynesian (Sandwich Islands) says that in 1860, one hundred and thirty whalers recruited at their island, and that in 1861 only sixty-nine recruited. The whole number of whalers north in 1861 was only seventy-six, and for 1862 the whole fleet north, so far as is known here, will only be thirty-three. During the coming spring we can only expect seventeen whalers to recruit here.”

- The Phillips Well on the Tarr Farm, drilled by William Phillips in 1861, became one of the most prolific oil wells in the Oil Creek region, producing up to 4,000 barrels per day at its peak. Discovered after Phillips observed an oily sheen on the Allegheny River, the well remained a dominant producer for nearly three decades and ultimately yielded nearly one million barrels before ceasing production in 1871. ↩︎