Heroism of Bad Bill Casey

The St. Louis Democrat, February 25, 1873

Among those killed in the railroad accident last week at Scrubgrass was William Casey, a character who richly deserves to be done up in verse; to have his name written in characters of living light in that book where the good and evil of man’s thoughts, words and deeds are recorded. Jim Bledsoe’s achievements were brilliant in their own way, and John Hay immortalized his name in verse. Poor Bill Casey, if I mistake not, will be denied a tablet to commemorate his virtues. Indeed, there are people in Oildom who to this day would say there is no need of it, for a single good virtue he never possessed. However, his career, which was one of crime and dissipation, terminated with an act so humane, so noble and so brave, as to show that in this cold, desperate man, there was the ring of the true metal of a generous heart.

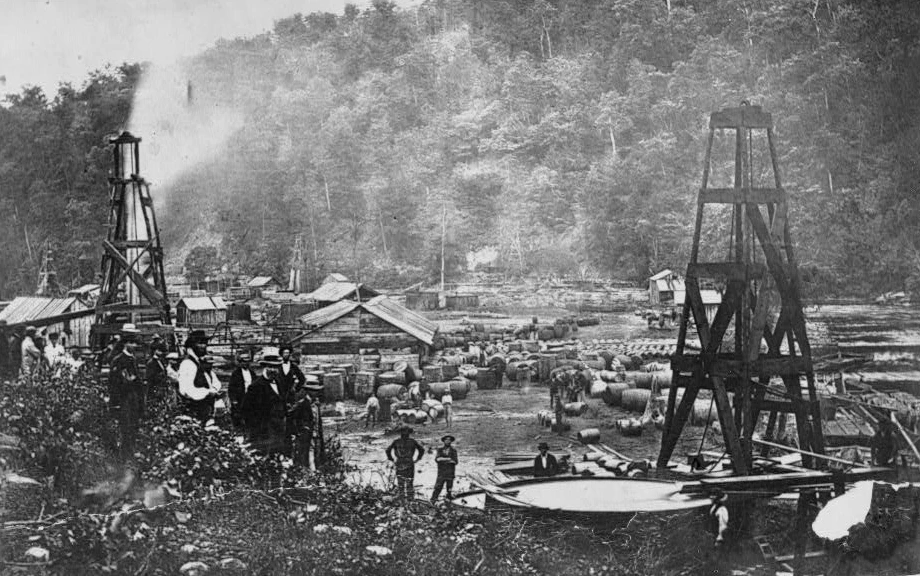

In the car, which was hurled over the bank into the river, where it landed bottom upward, were Casey and a number of prisoners. The fierce flame of petroleum surrounded the car on every side, but the occupants, Casey among the number, kicked out the windows, crawled out, and perched themselves on the trucks.

At this moment the pitiful cries of Jimmy Scott, a newsboy, were heard, too small to help himself from the wreck that entangled his legs. Casey made his way through the smoke and flame and water to where the little fellow was. He entered the wreck; in a moment afterward, there was a crash. The weight of the trucks had caused the bottom of the car to give way, and all within, three in number, perished.

After the fire had been extinguished the boy and Casey were found near each other, the latter fastened in such a manner in the wreck that he could not extricate himself. The fire had not touched a hair of his exquisitely arranged mustache, and he appeared so natural as to be easily recognized by his acquaintances. His neatly kidded hands were firmly clenched, and his arms were perfectly rigid and extended as in the act of clasping the child to his breast. His countenance wore a look of stern determination, as if the stubborn spirit had yielded to the relentless destroyer not without a fierce struggle.

Casey was about thirty-two years of age, a handsome, reckless, devil-may-care fellow, of splendid physique, and had the carriage of an autocrat. He had fought prize-battles, gambled for large and little stakes, and bore on his person as many scars from fistic and other encounters as the revolving turret of a war monitor. Only a few weeks ago, at Petrolia, he stabbed a man soundly in resentment for an insult that had been offered him, and the editor of a rural newspaper who commented on the deed was threatened with having his ears split, and sooner than have the operation performed, he filled up all available space in the next issue with dead advertisements.

Casey was devotedly attached to his aged mother, and though the years of his fast, fierce existence were spent with associations that cared little for God and less for man, he supported and provided her with every comfort until her decease about a year ago. The recording angel, surely, with the latest, and the noblest and bravest act of poor Bill’s sinful life, will drop a tear of pity over his errors and blot them out forever.