An American Baalbek

The Sun (New York), December 27, 1879

Aladdin’s Lamp in Northwest Pennsylvania: The Magic City That Arose Under the Wand of an Oil Magician – Wiped from Existence in a Year

“In that seat there by the stove,” said the conductor, pointing to a man with patched pantaloons and a slouch hat with a lock of hair sticking through a hole in the top. “Sitting there, with one arm on that oil-cloth carpetbag with the black worn off, is one-third of the population of the great city of Pithole.

“Shall I introduce you? Mr. Johnson, [this is] Mr. Perkins.”

“Then you are about all there is left in Pithole?” I remarked [to Mr. Johnson], as I sat down behind the man.

“No, thar’s twice as many as me thar. The Fergusons and Hunts, they are thar yet. Pithole suits them; they’re farmers. They are ploughing up the streets, and raising potatoes and corn where the Post Office and opera house were. Stop off at Oilopolis with me. I’ll take you over to see the ruins, if you’ll furnish the team.”

“All right, I’ll do it,” I said. And in two hours the horses pulled us from Oleopolis to the modern ruins of Pithole. Palmyra and Thebes are justly celebrated as very ancient ruins, but Pithole, Pa., is probably the grandest young ruin in the world. Here was a great city which was founded, grew to opulence, fell, and whose streets are now onion and cabbage patches – all within fifteen years. Why, it took those slowcoach Egyptians two thousand years to make such a ruin as this! Such is America’s enterprise.”

“When did you come here?” I asked Mr. Johnson, who acted in the capacity of both founder and guide to the ruins.

“I’m a carpenter, you know,” he said. “I first came here in 1865 to help put down the first well for the United States Petroleum Company on the Holmden farm. The country around here was almost uninhabited. The ground was stony, and the fields were full of pine stumps.”

“Did you strike oil?”

“I should say we did. We struck a ‘flow-er.’ She threw a thousand barrels of oil into the air a day. As soon as she ‘flowed’ the speculators went off in the night and bought the farm of Tom Holmden at a low figure. Lord! When he came to see the well the next morning didn’t he feel bad though!”

“What was the effect of the thousand-barrel well?” I asked.

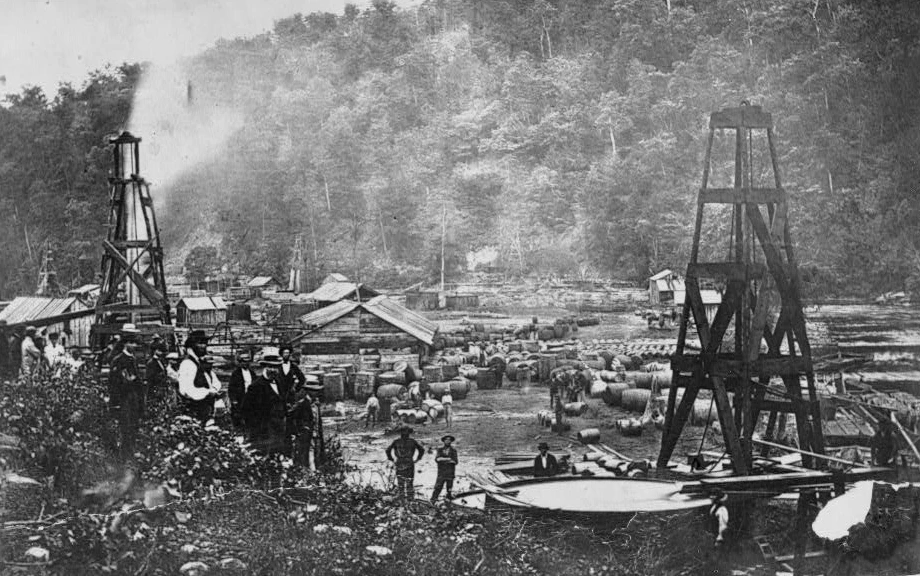

“Why, it seemed to set the whole neighborhood crazy. The whole oil region turned out and came up here. Soldiers with pockets full of money, just discharged from the army, came pouring in with the rest. In fact Tom Holmden’s farm, in less than 48 hours, looked as if it had ten circuses on it. You never saw such a scrambling.

“And prices! Why, you never heard of such prices. Twenty wells were underway in a week. Machinery had to be drawn through the mud from the station, on the Miller farm, four miles distant. Thousands of barrels of oil, worth $5 a barrel, had to be drawn through the mud. Farmers rushed in with teams for 50 miles around. Contractors paid $100 for drawing an engine four miles through the mud. Fifteen dollars a ton for drawing coal. Ten dollars for taking a trunk. Farmers got $10 for carrying one passenger. Two and three dollars were paid for meals, and five dollars for a bed.

“Dollars were as common as nickels are now. Why, I could make $25 a day carpentering. I got $650 for building a one-story building, and I did the work with four men in a day and a half. I got $45 for putting up some shelves for a druggist, and did this work in thirty minutes. Nails were fifty cents per pound, and lumber $300 a thousand. Farmers tore down their fences for miles around and sold them to the crazy oil operators.

“Great guns! How the merchants poured in! And what prices they got: $35 for a pair of boots, and a dollar for a drink of whiskey. Fortunes were made and lost in a day. Hundreds of wells went down and were sold at fabulous prices, afterward ending in dry holes.”

“How were the wells usually sold?” I asked.

“They were divided into ‘sixteenths.’ Thousands of soldiers, farmers, and business men were inveigled into buying these ‘sixteenths.’ Some made fortunes and more lost all. Speculators paid $500 for the refusal of a ‘sixteenth’ next to a producing well, telegraphed to New York or Philadelphia and made several thousand dollars in a few hours. A sixteenth of a well often sold for $20,000 cash.

Millions of dollars came floating into Pithole. Hotels went up like magic. Theatres sprang into thing. Murphy built a shanty, got a dance woman by the name of Mademoiselle Brignoli. Oil men would throw $50 bills at her feet. Streets sprang into line. Within 60 days, thirty pretty barmaids were holding forth at a free and easy. 7 First Street, all in a rude board room, 30 by 60.”

“When did Pithole culminate?”

“Well, she started in June 1865. In June 1866, she was a full-fledged city, with 15,000 people. With criminals, policemen, clergymen, churches, schools, and the third largest post office in the State of Pennsylvania. Why, Postmaster Hill had seven clerks, and to get a letter, you had to stand in a post office row for half an hour. We had a Mayor, a City Council, and daily newspapers.”

“Did you have any good buildings?” I asked.

“Certainly. The Duncan House, on First Street, cost $30,000. The Chase House cost over $60,000. Handsome business blocks went up, gas was put in, the streets were sewered … I tell you, we were a great city. People paid $2.50 for a seat at a variety show, and the town was filled with dance women and minstrels.”

“When did the decay come?”

“Oh, in 1867 we began to go down. Afterward, utter ruin came upon us. The oil wells stopped flowing, and we were ruined. They took down the Duncan House and moved it over to Oil City. The Chase House, which cost $60,000, was sold for $60. Many men burnt up their houses in 1867 to get the insurance, until no insurance company would take a risk in Pithole. In fact, everybody left Pithole as rats leave a sinking ship. The people who ran away from Pithole built up Shamburg, Titusville, Oil City, and Tidioute.”

I walked around Pithole, as I once walked Pompeii. The city is literally deserted. The houses are all tottering or fallen. Window panes are gone. No painter or glazier has been seen here for ten years. Fourth Street, once a thriving business street, has entirely disappeared. King’s hardware store has gone. The Record office has disappeared. The sidewalks have rotted away. And barren desolation meets me on every side.

On the hill, where the Atheneum used to be filled with a shouting audience who gathered to throw money at the feet of Maud Santley and a score of Black Crook dancers. I could see piles of potato vines where the farmer had dug his crop. Where Murphy’s Theatre once stood, and where the manager often took in as high as $2,000 during an evening, are bunches of burdocks and two old sandstones which denoted the corners.

“How many families are here now?” I asked Mr. Johnson, as I looked around at the ruins.

“Three. Only three. And still we represent all the political parties in the field. I’m a Democrat, Ferguson is a Greenbacker, and Hunter is a Republican. Don’t often happen, does it, that a founder of a city can take you around and show you the very ruins that he built himself? I tell you – why, damn it, of course nobody doubts that the Colosseum and Pantheon are grand old ruins. But when you talk about young ruins – splendid, young ruins – Pithole can buck up ‘ginst any en ’em!”